Nanoplastics may alter gut and liver metabolism depending on diet

Key takeaways

- A new study has found that low-dose nanoplastics altered gut and liver function in mice, disrupting gut barrier integrity, microbiota, and fat metabolism even without crossing the intestinal barrier.

- Western-style and standard diets changed how nanoplastics affected the gut microbiome and liver metabolism, influencing glucose intolerance and weight gain.

- Additive-free polystyrene nanoplastics alone were sufficient to trigger metabolic and digestive changes, challenging assumptions about food-grade plastics.

Researchers have uncovered that nanoplastics impact digestive health and liver metabolism in new mouse studies. This plastic residue, along with microplastics, is consumed through drinking water and packaged foods at amounts that have researchers worried. The implications of this reality for gut health have remained poorly understood until now.

Nutrition Insight speaks to the research experts at France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) to learn how diets and environmental exposures may lead to metabolic harm.

Over 90 days, mice were given various doses of nanoplastics — particles <1 μm in size — in their drinking water while on different diets. The researchers found that low doses altered gut barrier integrity and microbiota composition, with this effect more pronounced in mice fed a high-fat/high-sugar Western diet.

Disrupted fat metabolism and increased glucose intolerance also impacted liver function, regardless of diet. The researchers emphasize that this result occurred even though nanoplastics did not cross the gut barrier.

Challenging the inertia of plastics in food

The study in Environmental Science Nano used well-characterized, gold-labeled, and additive-free polystyrene nanoplastics (PS-NPLs). This enabled the researchers to study it independently of any plastic chemicals.

Plastics are often treated as inert in food systems. “From a nutrition and digestive health perspective, our results showed these additive-free PS-NPLs can compromise gut barrier integrity, modulate the composition and metabolic activity of the intestinal microbiota, and influence liver function,” says first author Muriel Mercier-Bonin, Ph.D., research director at the Toxalim Unit, and INRAE deputy director.

“Collectively, these findings challenge the long-standing assumption that food-grade plastics are inert, particularly when considered in their nanoplastic form.”

The importance of dietary patterns

The paper finds that nanoplastics’ effect on the gut depended strongly on dietary patterns. Corresponding author Chloé Liebgott, Ph.D., adds, for instance, that at the lowest PS-NPL dose, bacterial communities were distinctly affected by diet. She recently completed her doctoral research on nanoplastics and digestive health at the Toxalim Unit.

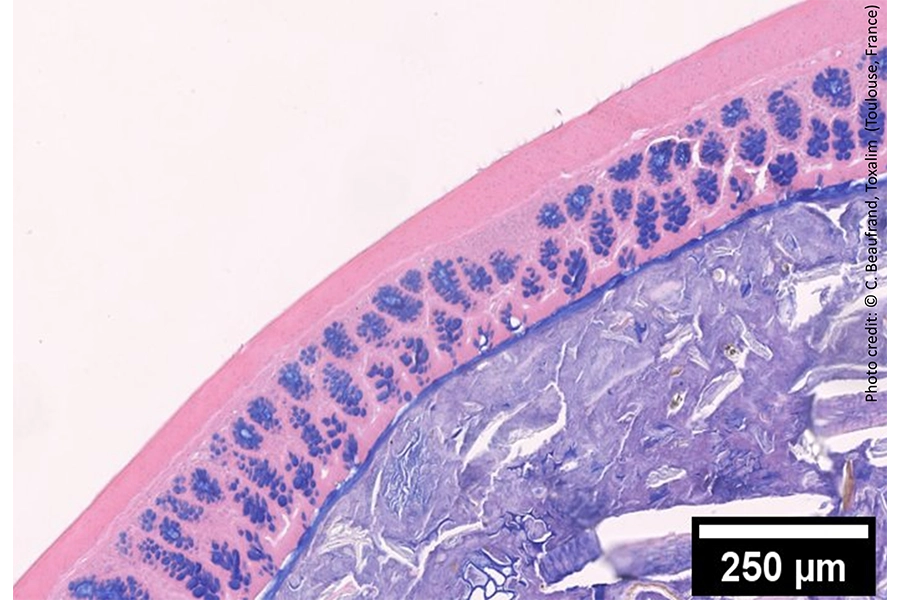

Longitudinal section of mucus layer (Image credit: INRAE).Liebgott says the team showed that low-dose PS-NPL exposure can alter digestive health in mice, regardless of diet — Western versus standard. The team considered three doses: 0.1 mg/kg body weight (bw)/day, 1 mg/kg bw/day, and 10 mg/kg bw/day.

Longitudinal section of mucus layer (Image credit: INRAE).Liebgott says the team showed that low-dose PS-NPL exposure can alter digestive health in mice, regardless of diet — Western versus standard. The team considered three doses: 0.1 mg/kg body weight (bw)/day, 1 mg/kg bw/day, and 10 mg/kg bw/day.

“The critical dose required to elicit hepatic effects was also modulated by diet: alterations were observed at the lowest dose — i.e., 0.1 mg/kg bw/day — under a standard diet, whereas under a Western diet, similar effects appeared only at 1 mg/kg bw/day.”

Mercier-Bonin suggests that the differences in diets may be due to physicochemical interactions between PS-NPLs and dietary components. This is because nanoplastics can interact with food substrates, especially fats. “Thereby modifying nanoplastics’ aggregation state, bioavailability, and biological impact on the gut barrier and liver.”

“Altogether, these findings highlight that diet can shape the toxicological outcomes of PS-NPL exposure, with implications for metabolic health in humans.”

Meanwhile, a different research team found that microplastics can alter the human gut microbiome, leading to patterns linked to depression and colorectal cancer.

An altered microbiome impacts the liver

Although the study found no indications that nanoplastics crossed the gut barrier, liver function was still affected.

Western-style diets amplified several digestive and metabolic effects of nanoplastic exposure.“We did not detect PS-NPLs in peripheral organs, even though we used inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry to detect and quantify nanoplastics in the whole organism of exposed mice based on the gold signature of the PS-NPLs used, a method renowned for its high analytical sensitivity,” comments Liebgott.

“However, we cannot rule out the possibility that some plastic particles can pass through the digestive barrier and reach the liver. If this hypothesis is verified, PS-NPLs could impact the liver directly. However, some indirect effects may occur.”

Mercier-Bonin adds that the literature on the gut-liver axis is well established, especially that changes in the microbiota affect liver function.

“For example, we observed that low-dose PS-NPL exposure induced a change in the composition of the microbial metabolites, such as bile acids or short-chain fatty acids, in mice fed a standard chow diet. These metabolites play a role in gut-liver signaling.”

Next step: Human exposure data

From a nutrition science standpoint, Liebgott and Mercier-Bonin say that nanoplastics’ exposure levels, long-term effects, and interactions with diet and the microbiome must be factored into assessments of their risk to human health.

“Indeed, the risk depends on exposure — to date, human exposure data are not known, and further research is required — and on hazards, focusing on long-term effects and taking into account the human exposome, which considers all environmental factors or stressors encountered throughout life,” says Liebgott.

“Our work shows that nutritional stress, such as the Western diet widely consumed in our Western societies, must be taken into account.”

Additive-free nanoplastics altered gut and liver metabolism in mice, with effects shaped by diet. Mercier-Bonin believes the research confirms the gut microbiota’s status as a major player in toxicology, as now acknowledged in physiology and pathophysiology, by showing its role in shaping composition and metabolic activity and in mediating observed effects.

Additive-free nanoplastics altered gut and liver metabolism in mice, with effects shaped by diet. Mercier-Bonin believes the research confirms the gut microbiota’s status as a major player in toxicology, as now acknowledged in physiology and pathophysiology, by showing its role in shaping composition and metabolic activity and in mediating observed effects.

Ensuring independent polymer effects

The researchers used additive-free nanoplastics to isolate the polymer’s effect. Mercier-Bonin explains that in literature, the question is whether the effects of nanoplastics are caused by the particles themselves or the chemicals present in the plastic formulation.

“Our work only allows us to examine the effects of the particle itself — which is submicron in size — using polystyrene as the polymer of interest.”

“This demonstrates that, in terms of health and safety, the influence of the particle must be considered, since smaller particles can more easily cross biological barriers — in our case, the intestinal barrier — and reach peripheral organs. This could inform a re-evaluation of existing literature data,” she concludes.

Previous research found that microscopic plastic particles in F&B may affect glucose metabolism and harm organs, such as the liver, in animal studies.