Cambridge researchers identify “hidden” gut microbes to unlock next-gen probiotics

Key takeaways

- Researchers link higher levels of the “hidden” gut bacteria group CAG-170 to better health, while low levels are associated with IBD, obesity, and other diseases.

- CAG-170 may support gut health indirectly by producing vitamin B12 and other metabolites that help beneficial bacteria function.

- The findings suggest a shift beyond traditional probiotics, opening the door to a new generation of therapeutics — despite major challenges in culturing and formulation.

UK research has found that healthy people’s gut microbiomes consistently have higher levels of the bacterial group CAG-170 than those with diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease and obesity. It reveals the importance of understanding the “hidden microbiome,” such as this bacterial group, to foster new therapeutics.

Nutrition Insight speaks with the lead researcher from the University of Cambridge to discuss the potential of CAG-170 to spur probiotic innovation and how the probiotics industry should broaden its applications beyond the well-known Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.

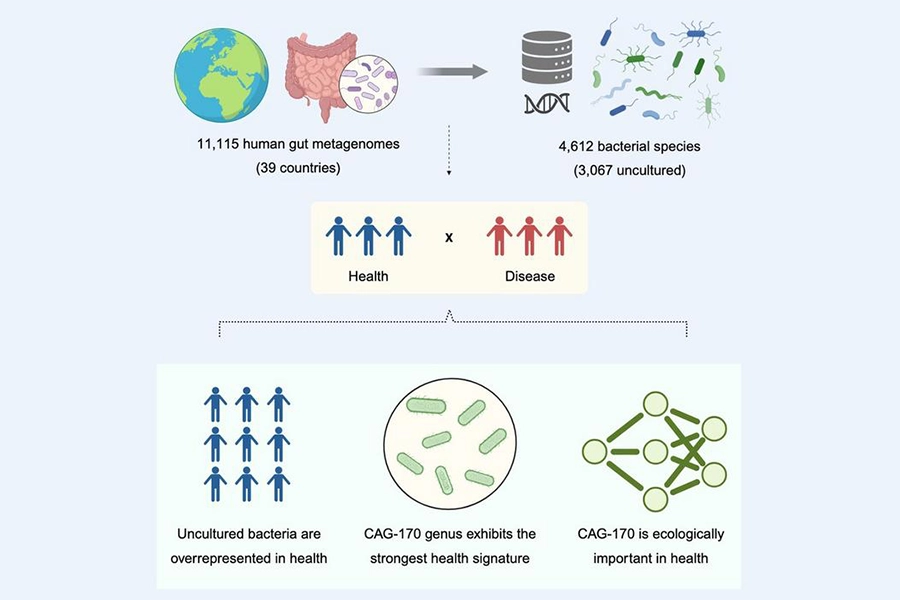

The team notes that CAG-170 may be essential for general health, boost digestion, and potentially produce vitamin B12. They analyzed gut samples from over 11,000 people across 39 countries and 13 diseases.

Additionally, the research suggests that CAG-170 could serve as a health indicator for the gut microbiome and that potential innovations could help maintain this group’s healthy levels.

The “hidden microbiome’s” potential

The Cell Host & Microbe study builds on research fellow Dr. Alexandre Almeida’s previous work, where he employed metagenomics to analyze the genomes of all the microbes in the gut, revealing 4,600 bacterial species, including the “hidden microbiome” of over 3,000 that had not previously been seen in the gut before.

“Our earlier work revealed that around two-thirds of the species in our gut microbiome were previously unknown. No one knew what they were doing there — and now we’ve found that some of these are a fundamental and underappreciated component of human health,” he says.

Furthermore, most CAG-170 strains have never been able to grow in the lab. “So far, researchers have successfully grown only one strain out of more than 300 strains identified to date. There are several reasons why CAG-170 has been difficult to culture.”

He explains that levels of CAG-170 are very low in the gut, making it hard to capture using standard laboratory techniques. The group is also sensitive to oxygen damage, so collected samples need to be processed rapidly. Lastly, it likely has special nutrition needs, which would require tailored laboratory conditions.

“One important clue from our work is that we found CAG-170 lacks the ability to produce arginine, an essential amino acid. Adding arginine to growth media may therefore help support its growth in the lab.”

“While these challenges have resulted in limited success so far in culturing CAG-170, they are not insurmountable. With improved methods and customized conditions, it may be possible to culture many more CAG-170 strains in the future,” he believes.

Potential commercialization of CAG-170

According to Almeida, it would be ideal to isolate and grow CAG-170 in the laboratory and formulate it into capsules to boost its levels in the gut.

The team looked at gut microbiome samples from over 11,000 people across 39 countries (Image credit: University of Cambridge).“First, researchers need reliable ways to isolate CAG-170. If it cannot be grown on its own under standard laboratory conditions, alternative strategies, such as growing it alongside other microbes, may help extract it and study it.”

The team looked at gut microbiome samples from over 11,000 people across 39 countries (Image credit: University of Cambridge).“First, researchers need reliable ways to isolate CAG-170. If it cannot be grown on its own under standard laboratory conditions, alternative strategies, such as growing it alongside other microbes, may help extract it and study it.”

“Second, although we observed strong associations between CAG-170 and health, extensive safety testing would be required before any potential commercial use. These tests would ensure that introducing CAG-170 into the gut would be safe and not cause harm. Finally, scientists still need to confirm that CAG-170 can successfully establish itself in the gut after being introduced,” he explains.

To reach success, scientists may need more strategies, such as pairing the group with dietary supplements, such as prebiotics, or delivering it with a selected mix of other microbial species to aid its growth.

CAG-170’s role

Almeida says his research has not yet identified the mechanism underlying CAG-170’s effects, as his team used correlational data. “However, our analysis points to a strong working hypothesis: CAG-170 appears to play an important role in keeping the gut ecosystem functioning smoothly.”

“This group of microbes seems to be key members of the gut community with a high capacity to produce vitamin B12. This vitamin is essential because many other gut bacteria rely on it as a helper molecule to carry out a wide range of important functions.”

It is likely that CAG-170 indirectly supports gut health by supplying metabolites to other beneficial bacteria, helping them thrive and remain functional.

Therefore, the most likely explanation is that CAG-170 supports gut health indirectly by supplying metabolites that help other beneficial bacteria thrive and perform their roles effectively.

Keeping up with research

The paper reveals that larger groups of understudied gut bacteria could play crucial roles in human health. Almeida points out that the probiotic industry has largely focused on Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which have been used for decades, but has not “kept up” with gut microbiome research.

CAG-170 has proven difficult to study because most strains cannot yet be grown in the lab, highlighting the technical hurdles facing next-generation probiotic development.“However, other species, including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and now CAG-170, are being linked to potential health benefits. One reason these microbes have not yet been widely developed as probiotics is the technical challenge of packaging them into capsules in a way that reliably keeps them alive and allows them to reach the colon, where they need to function.”

“As research advances, overcoming these challenges could open the door to a new generation of probiotics based on previously overlooked gut bacteria,” he believes.

On whether CAG-170 could be influenced by diet, Almeida says researchers do not know yet which diets or environmental factors increase bacteria in this group. However, it is an important question for future studies.

“What is clear, however, is that inflammatory conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with very low levels (or even a complete absence) of CAG-170.”

“One likely explanation is that inflammation alters the gut environment itself. Inflammatory responses can increase oxygen levels in the gut, which may eliminate microbes like CAG-170 that can only survive in oxygen-free conditions,” he concludes.