IIFH Discovery Forum: At the intersection of nutrition and health in the GLP-1 era

Key takeaways

- GLP-1 receptor agonists are revolutionizing obesity treatment, reshaping human health, and transforming global food and nutrition systems.

- Experts highlight their biological mechanisms, evolving formulations, and potential to inspire functional, metabolism-supporting food innovations.

- Nutrition remains essential alongside pharmacology to address side effects, nutrient deficiencies, and sustainable long-term weight management.

GLP-1 receptor agonist medications are transforming the food and health landscape with their ability to combat the obesity epidemic and change people’s relationship with food. The Innovation Institute for Food and Health’s (IIF) recent Discovery Forum explored how the science behind metabolic hormones can inspire a new wave of innovation in food for health.

Nutrition Insight attended the event from the University of California (UC) Davis, US, institute.

“We are at an incredible moment,” says Justin Siegel, Ph.D., IIFH faculty director. “It seems to me that this trend of using satiety-based drugs is starting to affect nearly every element of American — and worldwide — life.”

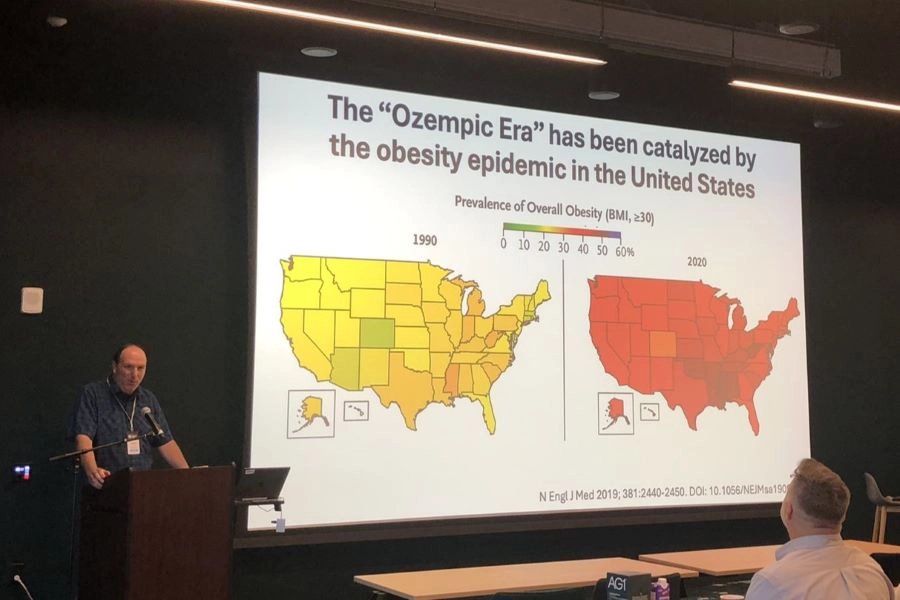

He says there has been a “tectonic shift” in human health. “In 1990, you could not find a single state in the US with an average body mass index (BMI) of over 25. In 2020, no state had an average BMI under that.”

“This isn’t just happening in the US; it’s global,” he underscores. “In 1990, hunger was the world’s biggest health issue. Hunger is still an issue in many places, but the global burden of human health is now obesity.”

According to Siegel, over the last 100 years, the medical system has focused on developing drugs to treat the consequences of “abusing our food system,” such as medication for blood pressure management or blood sugar control. Today, he says GLP-1 drugs help “blunt the cause” by helping to curb cravings.

“This is the first time in humanity that we’ve had tools to help change our relationship with food.”

Panel discussion with Justin Siegel, Sean Adams, Bethany Cummings, Kat Cole, and Mohamed Ali.He notes these people using these medications represent one of the most significant food accommodation needs, with 15 million Americans using them, and another 50% of adults being eligible for these medications.

Panel discussion with Justin Siegel, Sean Adams, Bethany Cummings, Kat Cole, and Mohamed Ali.He notes these people using these medications represent one of the most significant food accommodation needs, with 15 million Americans using them, and another 50% of adults being eligible for these medications.

“We’re looking at a future where we know that for a minimum of 5–6% of the population, and potentially half the population of the US, their relationship with food is changing,” he highlights.

“Just as the food system has moved to accommodate and adopt every other major dietary need, like kosher, low-sodium, keto, and gluten-free, we need to think about adapting the food system to the needs and desires of people using these drugs.”

Natural hormones versus drugs

Sean Adams, Ph.D., professor and vice chair for Basic Research at the UC Davis School of Medicine, explains that the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a major endocrine organ, with many cells secreting hormones relevant to food intake, regulation, energy expenditure, gastric emptying, and GI motility.

After a meal, different types of nutrients and metabolites can trigger these cells to produce hormones like GLP-1, peptide YY, GIP (gastric inhibitory polypeptide), and cholecystokinin. Meanwhile, the hormone ghrelin, released by the stomach, is reduced after eating.

Natural GLP-1 hormones can be degraded rapidly by an enzyme called DPP-4 (dipeptidyl peptidase-4). Adams explains that this prompted the creation of drugs like semaglutide, which are protected from DPP-4 degradation by manipulating the amino acids and adding a fatty acid.

“As a result, the pharmacokinetic profile of these drugs shows much higher concentrations of GLP-1 in the blood, for days on end. That’s why they work so well, they’re always there.”

“The concentration is about 1,000-fold higher than what we see from the natural hormone,” he adds. Siegel points to research findings that from 1990 to 2020, the average BMI in all US states increased drastically.

Siegel points to research findings that from 1990 to 2020, the average BMI in all US states increased drastically.

Adams says the variability in people’s drug response, in concentration and duration, also needs to be considered. “Maybe when people first inject the drug, they need different nutrition than when these drugs fade away in the bloodstream.”

“This could be a major consideration when designing functional foods, either intended to trigger natural GLP-1 release or considering the timing and types of nutritional interventions, that may matter just as much as anything else.”

New GLP-1 discoveries

Bethany Cummings, Ph.D., a professor at the UC Davis School of Medicine, explains that the GLP-1 hormone is secreted from specialized cells within the gut in response to eating a meal.

“GLP-1 has several actions: it increases insulin secretion, slows gastric emptying through the gut, and acts on the brain to reduce appetite. GLP-1 also has cardio-protective effects and indirectly improves insulin sensitivity throughout the body.”

“One of the most well-studied effects of GLP-1 is its incretin effect,” she explains. “It potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic islets, meaning that GLP-1 helps release insulin in response to meals. This effect accounts for up to 70% of our insulin secretion. The other main incretin hormone is GIP, produced by the gut, which is also of interest in pharmacology.”

Cummings notes that an emerging concept in GLP-1 physiology that her lab has worked on is that GLP-1 can be produced outside of the gut, such as pancreatic alpha cells.

“Classically, alpha cells produce glucagon, which raises blood glucose levels. However, there is a way to shift the alpha cell hormone production to produce GLP-1 instead. Essentially, this means there is a way to shift these cells from promoting diabetes to treating it. This is another potential target for these medications in the future.”

Additionally, she says more effective GLP-1 receptor agonists are being developed, including those that combine multiple agonists, which seem to provide even better results. “For example, tirzepatide activates both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, and early data suggest it may be more effective for weight loss than GLP-1 agonists alone.”

Addressing side effects

Mohamed Ali, professor and chief of Foregut of Metabolic and General Surgery at UC Davis Health, says that as a bariatric surgeon, he has seen its profound effects on patients regarding weight loss and diabetes remission.

He highlights that bariatric surgery provides a durable 25–30% weight loss. “It’s reasonable to think of this as the benchmark of all the tools we have today.”

The experts highlight the importance of nutritional support for people on GLP-1 medications, as they typically eat less and need to prioritize diet quality.“When you look at semaglutide as the medication we’re using a lot clinically, the data are really good, with patients who clearly, in excellent studies, demonstrate weight loss.”

The experts highlight the importance of nutritional support for people on GLP-1 medications, as they typically eat less and need to prioritize diet quality.“When you look at semaglutide as the medication we’re using a lot clinically, the data are really good, with patients who clearly, in excellent studies, demonstrate weight loss.”

However, these first-generation drugs are also linked to many side effects, such as GI intolerance, intestinal obstruction, lean mass loss, sarcopenia, vitamin deficiencies, and psychiatric concerns. Durability is also important in this conversation, as discontinuation of the medication results in rapid wave recurrence.

“Obesity is a chronic disease,” he stresses. “If you have a chronic disease, you should never stop treating it. Whatever medication you have, anytime you stop it, the disease comes back. But the problem is, most of the patients are not able to continue their medications.”

Nutritional support is crucial to address these issues. “When your volume is limited, the content you use for that volume becomes critical.”

Ali explains that preparation for bariatric surgery is comprehensive. Patients are evaluated by psychologists, attend nutrition classes, and meet with dietitians.

However, most GLP-1 prescriptions don’t come from comprehensive programs. Outside of specialized centers, doctors often recommend that patients take these medications if their insurance covers them.

Power of nutrition

Nutrient gaps endemic to modern society can worsen with appetite-suppressing drugs if the right dietary action isn’t taken. Kat Cole, CEO at AG1, says that the company’s supplement formulation is based on a lack of access and absorption of nutrients, acknowledging how the modern diet is not as nutrient-dense as it once was. “That was before we had a pharmacological intervention that would have us eat less and less.”

“People on these medications have less access to nutrients, and they’re experiencing GI distress more often. There is an even greater case for high-quality, nutrient-dense supplementation and gut health support, but in a format that people will adhere to.” Cole says that AG1’s all-in-one supplement powder mix combines micro- and phytonutrients, whole foods, and biotics as foundational nutrition.

Cole says that AG1’s all-in-one supplement powder mix combines micro- and phytonutrients, whole foods, and biotics as foundational nutrition.

Cummings agrees that nutrition should be the first defense for treating diseases like obesity. “When incorporating pharmacology, we should also be thinking about how we can adjust nutrition to support weight loss.”

Moreover, she cautions that GLP-1 production in the body is impaired by obesity. “These drugs are doing good work, but there’s still room to work within our own bodies and endogenous systems that would hopefully have fewer side effects and better adherence. The amplification of that internal system is going to come down to nutrition.”

Cole highlights three ways to help achieve this: boosting agriculture to produce more nutrient-dense foods, educating people to ingrain healthy habits, and promoting healthy lifestyles that people can adhere to.

“I want to see us continue the research in those areas of nutrition and lifestyle that are complementary to GLP-1, but may also prevent some of the terrible health outcomes that are decades in the making for the future.”