Dietary glycemic index is not an indicator of weight gain or loss, study finds

16 Aug 2021 --- A study has found that a high glycemic index, as a measure of carbohydrate quality, appears to be “relatively unimportant” as a determinant of body mass index (BMI).

The Arizona State University study findings conclude that high-glycemic (high-GI) foods – which are referred to as “fast carbs” – are no more likely than low-GI foods (often called “slow carbs”) to lead to weight gain. Also, these foods are no less likely to lead to diet-induced weight loss.

“The results of our review confirmed what we had seen in previously published research. Glycemic index (GI) is relatively unimportant in terms of weight loss and obesity prevention,” Glenn Gaesser, co-author of the study and professor at College of Health Solutions, Arizona State University tells NutritionInsight.

“Our review of the literature shows that GI is not a very important factor when it comes to body weight, whether it is for obesity prevention or weight loss. GI might have value for improving chronic disease risk, but its effects are complex,” he adds. In terms of weight loss and obesity prevention, the study reports glycemic index is relatively unimportant.

In terms of weight loss and obesity prevention, the study reports glycemic index is relatively unimportant.

“We’ll start to see data that moves beyond merely classifying carbs as simple or complex (fast or slow). Carbs form the backbone of diets worldwide, and there is an urgent need to move beyond reductive messaging that does not convey useful information to the consumer.”

Assessing glycemic index

The comprehensive study analyzed data on 43 cohorts from 34 publications, which comprised nearly two million adults, to assess if dietary glycemic index impacts body weight.

The study was undertaken to assess the hypothesis that high-GI foods promote fat storage and increase the risk of obesity by causing a rapid increase in blood sugar and insulin secretion and that low-GI foods do the opposite.

“GI is a good example of a ‘measure’ that is highly variable and often not particularly useful at the individual level due to substantial variability. The sector is moving toward better defining carbohydrate quality,” says Julie Miller Jones, co-author of the study and professor of nutrition at the Department of Family, Consumer, and Nutritional Science, St. Catherine University.

“However, it is important to remember that this is a complex issue that defies easy solutions. Our findings demonstrate that the food and health industries would be ill-advised to use the GI to create nutrition guidelines for consumers concerned with their body weight.”

The study is published in Advances in Nutrition and funded by the Grain Foods Foundation, which offers research-based information and resources on grains and nutrition.

Zoning in on previous findings

In the 27 cohort studies that reported results of statistical comparisons, 70 percent showed that BMI was either not different between the highest and lowest dietary GI groups (12 of 27 cohorts) or that BMI was lower in the highest dietary GI group (seven of 27 cohorts).

Results of 30 meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from eight publications demonstrated that low-GI diets were generally no better than high-GI diets for reducing body weight or body fat..jpeg) The study emphasizes that researchers and nutrition communicators need to be mindful of the benefits of carbohydrates.

The study emphasizes that researchers and nutrition communicators need to be mindful of the benefits of carbohydrates.

Although low-GI diets with a dietary GI at least 20 units lower than the comparison diet resulted in more significant weight loss in adults with standard glucose tolerance. However, it did not do so in adults with impaired glucose tolerance.

“The review reminds us of the many other qualities of carbohydrates that are far more important to consider: for example, nutrient density, dietary fiber and whole grain content, and percentage of added sugar,” says Siddhartha Angadi, co-author and assistant professor of education at the Department of Kinesiology, University of Virginia.

Carbohydrates in focus

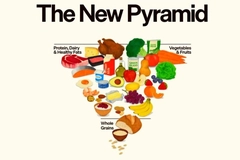

The study highlights the need for both researchers and nutrition communicators to be mindful of the many positive nutrients that staple carbohydrate foods contribute to diet quality when characterizing or communicating the quality of carbohydrates.

“We think it misleads consumers to talk about ‘good’ carbs and ‘bad’ carbs. There are only good diets and bad diets. Good diets include all food groups in the right balance, contain all the essential nutrients including dietary fiber, and also have calorie amounts that are appropriate for age, gender, and physical activity level of the person,” adds Angadi.

Industry players have been voicing the complex nature of diets and also supported glycemic control. In this space, a study conducted by the National Institutes of Health found that weight loss is more complicated than previously imagined.

To further develop this industry segment, DSM supported Phynova’s glycemic control component with a €10 million (US$ 11.7 million) investment last year.

By Nicole Kerr