Body ideals, lack of regulation could harm those with muscle dysmorphia, experts flag

.jpg)

21 Mar 2022 --- Muscle dysmorphia is an under-studied psychological disorder that is rising among young men and boys. The condition is associated with excessive protein consumption and supplements use, and its emergence could have implications for industry, as lack of regulation gives users unfettered access to products promising to achieve their body goals.

NutritionInsight speaks to experts on what the impact of this condition is, as well as how lack of regulation and body ideals could be playing a role in the disorder’s proliferation.

“Most supplements can be bought online or over the counter with little to no regulation. Studies analyzing these products have found that many are mislabeled and are tainted with harmful substances like anabolic steroids,” says Dr. Jason Nagata, assistant professor of pediatrics for the division of Adolescent & Young Adult Medicine at University of California.

“In the long term, anabolic steroids can lead to kidney problems, liver damage and heart disease.”

Health to the point of harm

Muscle dysmorphia occurs when an individual becomes obsessed with becoming muscular, Nagata explains.

“They may view themselves as puny even if they are objectively muscular. People with muscle dysmorphia may use anabolic steroids or other appearance- and performance-enhancing drugs to become more muscular. They may engage in excess exercise.”

While there is rising concern for men, appearance-related psychological disorders of all kinds are prevalent in higher rates among women.“Red flags for muscle dysmorphia are when a person becomes preoccupied with their appearance, body size, weight, food or exercise in a way that worsens their quality of life. They may withdraw from usual activities or friends because of concerns with body size and appearance,” he adds.

While there is rising concern for men, appearance-related psychological disorders of all kinds are prevalent in higher rates among women.“Red flags for muscle dysmorphia are when a person becomes preoccupied with their appearance, body size, weight, food or exercise in a way that worsens their quality of life. They may withdraw from usual activities or friends because of concerns with body size and appearance,” he adds.

According to Nagata, sufferers take standard health advice to the extreme to achieve body goals in a way that is harmful to their health in the long run.

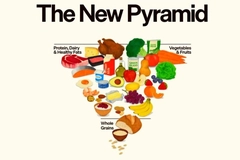

“People with muscle dysmorphia may consume high-protein diets while cutting carbohydrates and fats in pursuit of muscularity. They also may not consume enough nutrition to meet the energy demands from excessive exercise, leading to a relative energy deficiency.”

Associated with protein and creatine supplement-use

Nagata elaborates that in scientific literature, the disorder is linked to muscular body ideals in men and boys.

“The idealized masculine body is big and muscular. Nearly a third of teenage boys report they are trying to bulk up or gain weight.”

This standard is having an impact on young men in particular, who are taking increasing steps to achieve this ideal: “22% of young men report taking supplements, steroids or eating more to bulk up,” says Nagata.

He highlights that those with muscle dysmorphia are especially prone to consuming certain supplements.

“Use of protein and creatine supplements are linked with muscle dysmorphia and eating disorder symptoms,” he notes, lamenting the ease of access to consumers.

A disorder of self-perception

According to Rachael Flatt, MA of clinical psychology, pop-culture terms for the disorder like “bigorexia” are not preferred by psychologists or patients. Further, the term is a misnomer, as it creates the idea that muscle dysmorphia is an eating disorder like anorexia or bulimia.

In reality, muscle dysmorphia is not an eating disorder but a disorder of self-perception, which has high comorbidity with eating disorders and extreme diet and exercise habits. Further, muscle dysmorphia is not a stand-alone disorder, but a subcategory of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). Body dysmorphic disorder has existed as a diagnosis since the 1800s.

Body dysmorphic disorder has existed as a diagnosis since the 1800s.

This is according to Kitty Wallace, head of operations at the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Foundation, who tells NutritionInsight: “BDD is not a new condition; in fact, it was first diagnosed in 1891 by the psychiatrist Enrico Morselli.”

She continues: “It is an anxiety disorder that is characterized by a preoccupation with one or more perceived defects or flaws in appearance. The preoccupation can be with any part of the body but is most common with the skin, nose, eyes or overall body build. In ‘bigorexia,’ the focus is on the size of muscles.”

Treating muscle dysmorphia

According to Wallace, treatment for muscle dysmorphia is the same as for BDD. This is specialized cognitive behavioral therapy, a common therapy that helps individuals reform mental schema through therapy sessions and exercises.

“This would be tailored to each individual and their particular preoccupation.”

However, tailoring said rehabilitation is difficult when little targeted information on the disorder exists within the scientific literature.

“Unfortunately, there is still a need for more research on nutritional rehabilitation, treatment, and medical management of muscle dysmorphia,” says Nagata.

“Research into BDD is extremely lacking, even in western countries. Specific research into muscle dysmorphia is even less,” echoes Wallace.

In January, the FDA flagged the US market was flooded with questionable quality supplements; in response, the American College of Clinical Pharmacology called for greater regulation to protect consumers.

Recently, NutritionInsight held a roundtable on how consumer groups and regulations were set to transform the active nutrition space.

By Olivia Nelson